Monday, December 19, 2016

Toxic Textiles: Book review of Fake Silk

Book Review. Below is an excerpt from my recent review of:Fake Silk The Lethal History of Viscose Rayon Paul David Blanc, Yale University Press. The review first appeared in Science, 25 Nov 2016:Vol. 354, Issue 6315, pp. 977

In this slim, action-packed book, Paul David Blanc takes the reader on a historical tour that touches on chemistry, occupational health, and the maneuverings of multinational corporations. Our guide is a small, “elegant” molecule called carbon disulfide—a compound that is a key ingredient in the making of viscose (better known as rayon) and is also insidiously toxic, having devastated the minds and bodies of factory workers for more than a centuryFake Silk: The Lethal History of Viscose Rayon unveils a story that, in Blanc’s words, “deserves to be every bit as familiar as the cautionary tale of asbestos insulation, leaded paint, or the mercury-tainted seafood in Minimata Bay.” Who knew that the fabric that has had its turn on the highfashion runway, as a pop-culture joke (remember leisure suits?), and more recently as a “green” textile had such a dark side?

Rayon is a cellulose-based textile in which fibers from tree trunks and plant stalks are spun together into a soft and absorbent fabric. First patented in England in 1892, viscose-rayon production was firmly established by the American Viscose Company in the United States in 1911. Ten years later, the factory was buzzing with thousands of workers. “Every man, woman, and child who had to be clothed” were once considered potential consumers by ambitious manufacturers.

However, once the silken fibers are formed, carbon disulfide—a highly volatile chemical— is released, filling factory workrooms with fumes that can drive workers insane. Combining accounts from factory records, occupational physician’s reports, journal articles, and interviews with retired workers, Blanc reveals the misery behind the making of this material: depression, weeks in the insane asylum, and in some cases, suicide. Those who were not stricken with neurological symptoms might still succumb to blindness, impotency, and malfunctions of the vascular system and other organs. For each reported case, I could not help but wonder how many others retreated quietly into their disabilities or graves.

Yet, “[a]s their nerves and vessels weakened, the industry they worked for became stronger,” writes Blanc. In Fake Silk, he exposes an industry that played hardball: implementing duopolies and price-fixing and influencing federal health standards. For more see here. (Though you may need a subscription or library to access the rest.)

Thursday, December 15, 2016

An antibiotic alternative? Hope through science.

|

| Antibiotic resistance test. Image: Dr. Graham Beards |

A toddler suddenly becomes deathly ill. In the ER she is diagnosed with dysentery, caused by a rare but particularly aggressive form of Salmonella. One antibiotic after another fails because the strain, picked up when her family was traveling across parts of Asia, resists multiple antibiotics; but there is an alternative new drug. Like a guided missile, the drug targets only the disease causing Salmonella. Not only that, but as long as Salmonella remains, the drug particles replicate, increasing in number until the infection subsides. Despite the carnage, the toddler’s gut microbiome remains unharmed – no need for probiotics or fear of complications like C. diff. If Salmonella responds by evolving resistance, the drug may respond in turn engaging an ages old evolutionary dance. By the next morning the color returns to her cheeks. By evening, she is cured.

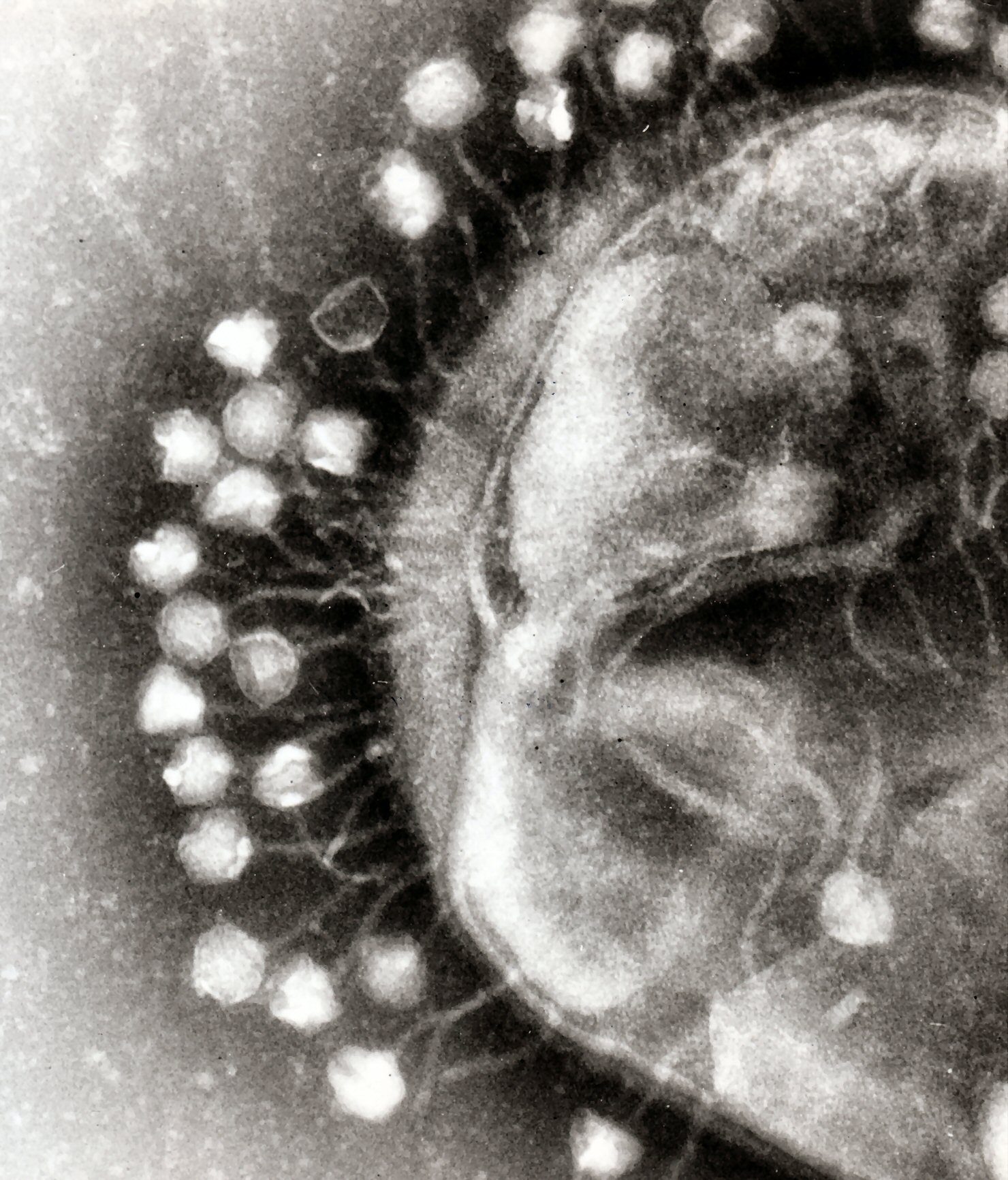

While still a fantasy here is the U.S., the scenario has been playing out in Eastern European hospitals and clinics for nearly a century. The “new” drug is a virus called a bacteriophage (or simply “phage”), that attacks bacteria. It is a cure nearly as old as life; at least as old as bacteria. Microbiologists have suggested that for every strain of bacteria on earth from the oceans to those populating our own microbiomes– there is at least one, if not multiple bacteriophages.

- Viral phages infecting a bacterium. Image: Dr. Graham Beards

As diseases like TB, gonorrhea, E.coli, staph and other common infections increasingly evolve to resist our antibiotics, health care workers are fast becoming desperate for new antimicrobials that are both effective and cause minimal damage to our own microbiomes. Bacteriophages are potent antimicrobials. Once disparaged here in the U.S. and in western medicine in general, these bacteria infecting viruses are making their way back into academic and biotech laboratories. If all goes well, they may be coming to a pharmacy near you.

We now know that throughout our existence viruses have woven in and out of life – leaving their stamp on most if not all living things. By some accounts up to eight percent of our genetic material came to us by way of viruses. Yet for all the fear and harm we associate with viruses many (if not most) are phages, infecting bacteria, like those in our microbiome. Genomics is just beginning to reveal the diversity and representations of these entities in nature and within our bodies. But the role that phages can serve as potent antimicrobials is no mystery. As infectious agents of bacteria they are a normal and pervasive component of earth’s flora, and they have already saved countless lives. One day they just might save us or our loved ones.

This is only one solution. There are plenty of others in the works. Lets just hope they get the funding they need in the coming years.

Adapted from Natural Defense: enlisting bugs and germs to protect food and health (Island Press, Spring 2017.)

Labels:

antibiotic resistance,

antimicrobials,

bacteria,

health,

virus

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Raisin Hell (and Dogs)

(Cross-posted from toxicevolution.)We were closing in on the end of a glorious spring weekend when my husband discovered the bag. “Any chance you left this lying around — empty?” he’d asked holding the remnants of a one pound bag of Trader Joe’s raisins I’d purchased just the day before with images of molasses filled hermit cookies in mind. I hadn’t, nor had I made the hermits, or chewed away the corners of the bag. Apparently Ella (pictured above) had consumed every last raisin, save the two handfuls my husband snacked on before leaving the bag on the living room floor.

(Cross-posted from toxicevolution.)We were closing in on the end of a glorious spring weekend when my husband discovered the bag. “Any chance you left this lying around — empty?” he’d asked holding the remnants of a one pound bag of Trader Joe’s raisins I’d purchased just the day before with images of molasses filled hermit cookies in mind. I hadn’t, nor had I made the hermits, or chewed away the corners of the bag. Apparently Ella (pictured above) had consumed every last raisin, save the two handfuls my husband snacked on before leaving the bag on the living room floor.

“I bet she won’t be feeling too good later,” he’d said, eyeing the ever expectant dog sitting at our feet, tail wagging, hoping for a few more of the sweet treats. He had no idea. Nor had I. Not really. I’d had some inkling of a rumor that raisins and grapes were bad for dogs, but never paid too much attention. It’s one of those things you hear at the same time you hear of people treating their dogs to grapes. So, to be safe (and feeling a bit sheepish that, as a toxicologist I ought to have an answer to the raisin question) I suggested he call the vet. And that is when we fell into the raisin hell rabbit hole. Five minutes later dog and husband were on their way to the doggie ER, pushed ahead of the mixed breeds and the Golden and the sad-sack blood hound and their people waiting for service.

Meanwhile I took to Google. Was this really a life or death dog emergency? If so, why weren’t we more aware? I get it, that one species’ treat can be another’s poison. Differences in uptake, metabolism, excretion. Feeding Tylenol to cats is a very bad idea (as if you could feed a cat a Tylenol tablet). And pyrethrin-based pesticides in canine flea and tick preventions are verboten in felines. The inability to fully metabolize and detoxify these chemicals can kill a particularly curious cat. But raisins in dogs? Not so clear. Googling will either send you racing off to the vet or to bed. You may even toss your best friend a few grapes for a late night treat, smug in the knowledge that those who have bought into the hysteria are hemorrhaging dollars while paying off the vet school debt of a veterinarian who is gleefully inducing their dog to vomit, while you snooze.

Even Snopes the online mythbuster was confused (though they suggest erring on the side of caution.)

By the time I arrived at the clinic, uncertain enough to follow up on husband and dog, Ella’s raisin packed gut under the influence of an apomorphine injection (a morphine derivative which induces vomiting in seconds) had done its thing. While Ben and I waited for Ella’s return in the treatment room, somewhat relieved, we played, “Guess how much?” Treatment with a drug, time with the vet, multiplied by the “after hours factor” this being a Sunday evening after all, we’d settled on something in the $300-400 range.

“Ella did great,” said the vet tech who’d taken her from Ben and hour or so earlier. “A pile of raisins came up. Some were even still wrinkled!” Phew. Potential disaster averted. We’d accepted that it’d likely cost a few hundred – but we’d soon be heading home with Ella in the back seat. We had a good laugh about the revisit of the raisins. But the vet tech wasn’t finished. That was just the first step. “So now we’ll give her some activated charcoal,” she continued “and you can pick her up on Tuesday.” Total estimated low-end estimate? A bit over $1000. Paid up front (I have wondered what would have happened if we couldn’t pay – but that is a whole other issue). Apparently we had underestimated the price of a good vomit.

“We can’t be sure we’ve got all the raisins. So we treat with aggressive I.V. Two days is the standard minimum.” Noting our jaws dragging on the floor, or maybe my comment “that’s a plane ticket to Europe” she added, looking at us a bit less sympathetically. Adding “well, of course you can take her tomorrow, or even tonight….if that’s what you want. But that’s what we do. You can talk about it with the Vet.” Or, sure, go ahead take your chances. Poor dog.

Emetics like apomorphine, according to the literature, are only good for purging 40-60% of a dog’s stomach contents. So, even a good barf, will likely leave some raisins behind.

Two days though? With I.V? While waiting for the vet another bout of Googling confirmed the standard treatment. Induce vomiting, charcoal, two days of IV and kidney chemistry panel. Ouch.

But, here is the kicker: no one in the whole Google universe could tell me why we were doing this. Why the fruit we take for granted in our cookies can kill our dogs. The virtual gauntlet thrown, I took the challenge. Surely the scientific literature sitting behind a pay wall would provide the answer. But even in my go to database, the Web of Science a site that normally yields more far papers than I care to even skim their titles – there were a handful of articles. Yet there was evidence of poisonings: one article reported kidney failure in a Shih Zhu and a Yorkie in South Korea. Another wrote of a Norwegian elkhound, lab, Border collie and a Dachshund all poisoned by raisins. The most popular article, published over ten years ago focused on 43 cases of renal failure following raisin consumption drawn from a decades’ worth of reports to the AnTox database (sponsored by the ASPCA).

That study confirms renal failure following raisin ingestion. Since all dogs in the study were already presenting with symptoms the authors couldn’t provide information on what proportion are sensitive. Though they acknowledge that there are plenty of anecdotal dogs for whom grapes and raisins are a risk-free treat. They also suggests there is no correlation between amount of raisins ingested and degree of kidney toxicity. In other words there is no dose response. That alone is enough to confound a toxicologist (dose response is a basic tenet of toxicology, the dose makes the poison and all that), and spark controversy amongst dog owners. A dog can eat a few and die. Or eat a whole 16oz bag, and get by with or without treatment depending (albeit with the upset to be expected after eating a heap of dried fruit.) Not only that, but no one know why raisins cause kidney failure. There have been plenty of guesses: fungal toxins; pesticides; something intrinsic to a particular variety; or canine genetics. But there just isn’t enough consistency to identify a mechanism of toxicity. And so vets err on the side of caution.

One vet tells me her dog went into kidney failure after eating some grapes she discarded (she managed to save the dog). Another says she’s never seen a dog with raisin toxicity (of course absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence – but those dogs who can eat grapes and not die, won’t show up on the vet’s doorstep either.)

“Sorry to hear about your dog’s experience with raisins,” writes veterinary toxicologist John Babish writes after I’ve emailed him about Ella’s ordeal (John was my advisor while in graduate school at Cornell University) asking: what’s up with the raisins?

“The same thing can occur with grapes – all kinds and colors. Canine responses to grapes and raisins are highly variable and some dogs are not affected at all – about 30% are sensitive to very sensitive and a clear majority do okay with no effects. A negative fallout of the inconsistency of response is that some bloggers maintain that grapes/raisins are not toxic to dogs.” Which explains blogs and websites like the Dog Place posting Snopes and ASPCA Poison Control Urban Legend; Poisoned by Grapes, NOT; Grape/Raisin Debate; or No More Vet Bills,Grapes Toxic to Dogs?

We are not used to uncertainty. We live in a high-tech age of data. We can sequence the human genome and create disease resistant rice. We can measure toxic substances down to the parts per quadrillion (trust me, that’s a really small amount,) and tease apart the inner workings of our cells in detail unimagined even a decade ago. But sometimes you have to make a decision with the information you have. We weren’t willing to bet that Ella was in the majority.

Two days later we collected our pooch, happy as ever and oblivious to the whole ordeal. We won’t ever know (I hope) if she is in the minority of dogs who can’t handle their grapes and raisins; or if that $1000 worth of purging saved her life, or simply emptied our wallet. But, just in case – that replacement bag of raisins I bought? Those will remain on the top shelf hidden away until I get the urge to make some hermits.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)