|

| Antibiotic resistance test. Image: Dr. Graham Beards |

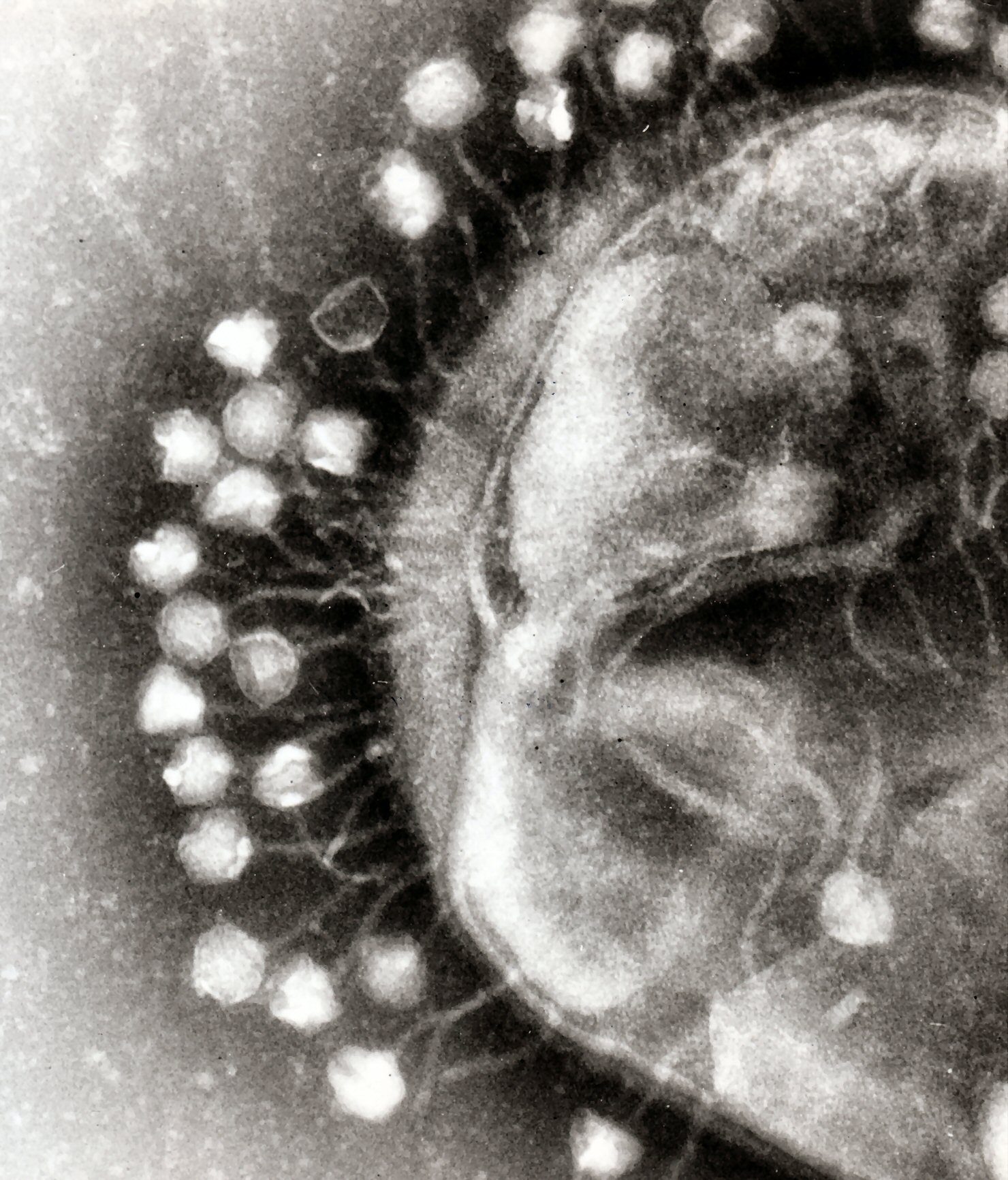

- Viral phages infecting a bacterium. Image: Dr. Graham Beards

The Neighborhood Toxicologist summarizes information on chemical contaminants that impact our daily lives and our environment.

|

| Antibiotic resistance test. Image: Dr. Graham Beards |

Toxicology: the study of the adverse interactions of chemicals with dynamic living systems. We are all exposed to a diversity of chemicals (often as chemical mixtures) through our diet, the pharmaceuticals we use, the air we breath, and the water we drink. While toxicologists usually study xenobiotics or chemicals “foreign to living systems,” it’s worth noting that in some cases, chemicals as familiar and as natural as water can be toxic.

Some history: Toxicology as a formally recognized scientific discipline is relatively new (mid 1900’s) although the science itself is thousands of years old. Consider the potential results of early trial and error experiences of hunter-gatherers for whom identifying a toxic plant or animal was a life or death situation. Some of the most poisonous substances known today are naturally produced chemicals including Ricin from castor beans or tetrodotoxin from the puffer fish. Early humans’ careful observation of plants or animals with toxic characteristics such as frogs containing curare, were put to use not only for avoidance of toxic substances but for weapons as well. Additionally, many naturally derived poisons were likely used for hunting, medicinals (the Egyptians were aware of many toxic substances such as lead, opium and hemlock as early as 1500 BCE), and eventually for the political poisonings practiced, for example, by the early Greeks and Romans.

As humans sought to better understand natural compounds that were both beneficial and harmful, there was very little if any clear understanding of the fundamental chemical nature of substances. That is, there was no connection between the ‘extract’ or ‘essence’ of a poisonous plant or animal and any one particular chemical that might cause toxicity. In fact, an awareness of chemistry in its modern form did not occur until the mid to late 1600’s[i]. So it is ironic that Paracelsus, a physician from the sixteenth century and one of the early “Fathers of Toxicology” had no clear understanding of chemistry as we know it today. He along with many others at that time apparently believed that all matter was composed of three “primary bodies” (sulfur, salt, and mercury)[ii]. Yet Paracelsus also coined the now famous (or infamous) maxim of the newly emerging discipline of toxicology:

“All substances are poisons, there is none which is not a poison. The right dose differentiates a poison from a remedy.” (Paracelsus,1493-1541)

This phrase and Paracelsus’ name are committed to memory by hundreds of new toxicology students each year and has become the ‘motto’ of toxicology. Interestingly, if one takes Paracelsus at face value, it appears he was referring to potential remedies. This is an important point, since in recent years some have turned this around to suggest that exposure to very small doses of highly toxic chemicals (such as dioxins) might not be an problem! These days most of us are well aware of the fact that overdosing can turn remedies to poisons, even with apparently innocuous drugs such as aspirin and Tylenol.

[i] Ball, P. 1999. Life’s Matrix: A Biography of Water. Farrar, Straus and

[ii] Ball, 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment